A Visual Story of the Sacandaga

By Joanne E. McFadden

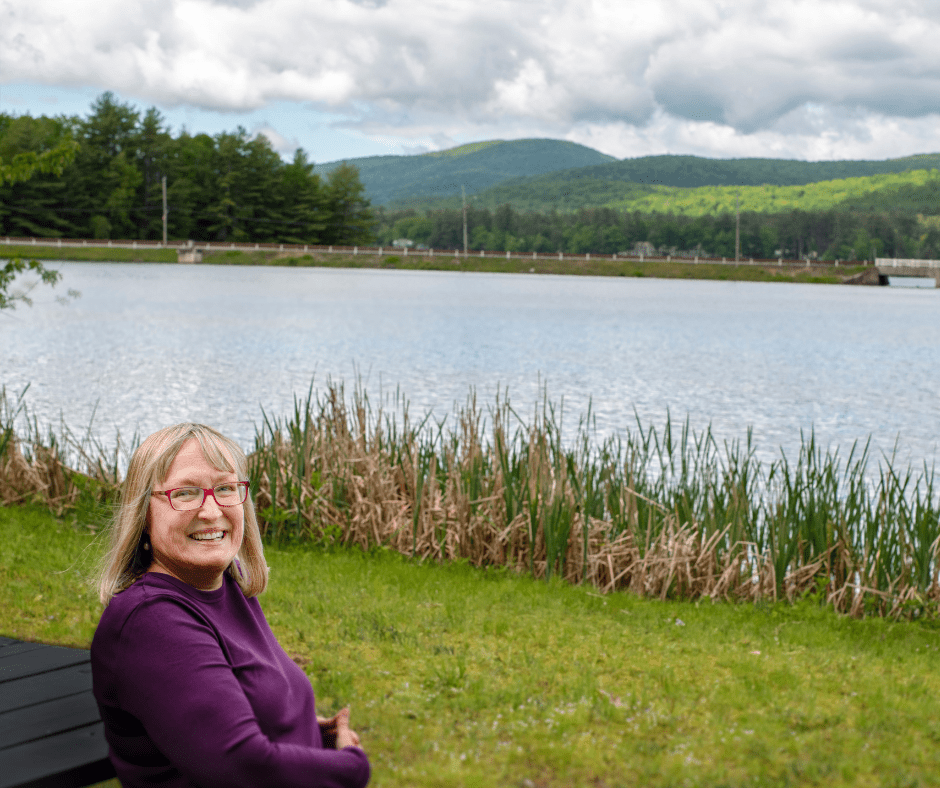

Linda Finch of Northville is a versatile artist. She works with a variety of media, including metal, wood, resin, plaster, clay, and paint with various techniques. Her work also demonstrates a wide range of styles. Her latest works speak not only to art, but to the history of the region in which she lives.

Finch grew up in the southern Adirondacks and Mohawk Valley, and her family has a long history here. She herself has lived in several places, including California, the Southwest, Maryland, St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Dauphin Island, and New York’s Southern Tier. It wasn’t until she moved home in 2018 that she truly began to appreciate the vibrant history of the area as well as her family’s own personal history here. Even though she was born and grew up in the area, Finch said that she somehow missed “what a phenomenally historic place this was.”

Finch believes that documenting this history is extremely pertinent in a time when things are changing so rapidly as a result of the pandemic bringing an influx of new residents from outside the area.

With fresh eyes and a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts just as the COVID-19 pandemic set in, Finch set about documenting the region’s history with a series of eight folk art paintings. However, when the pandemic lockdown continued, Finch just kept painting, even though she had fulfilled the grant’s requirements. She now has a collection of over 18 works telling the story of the area. “It was so strange,” Finch said. “Just because I was so quarantined, instead of living a normal life, I was just painting every day,” she said.

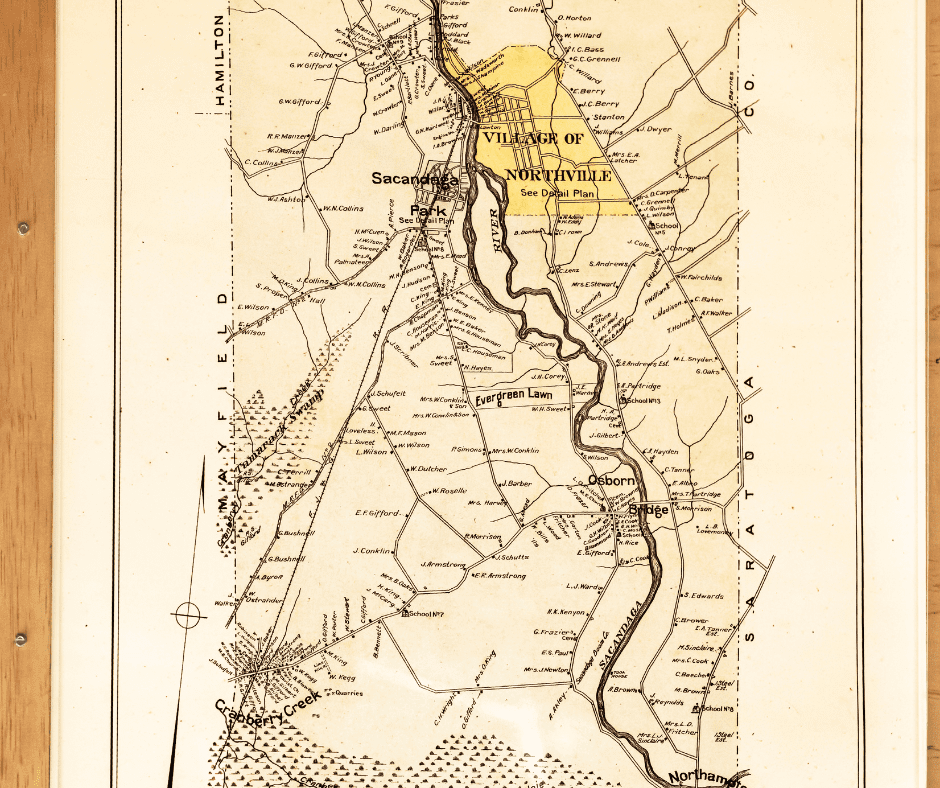

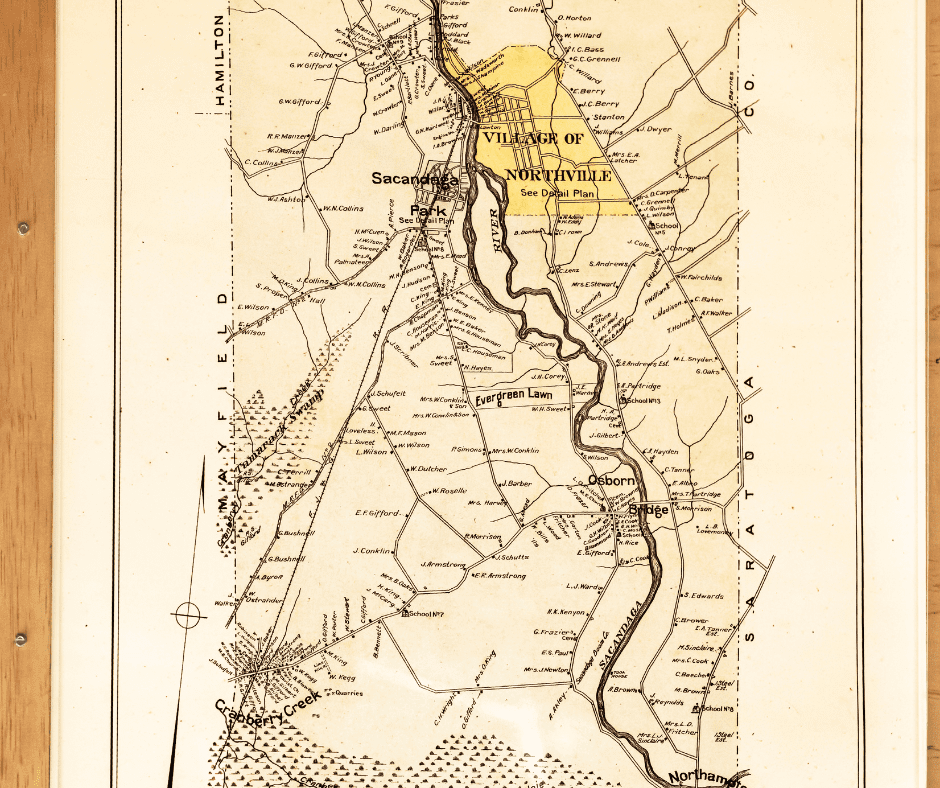

Research became an extremely important part in the process of accomplishing her goal of preserving the area’s history with accuracy, and she spent months researching each painting. For example, Finch interviewed a 101-year-old friend who visited the park as a child to find out where various attractions had been located, such as the carousel, animals, and “Shoot the Shoot” toboggan slides. She also had a collection of family stories and photographs, as well as the resources of local historical societies that provided maps and background information about the area’s architecture, planning, and other history. “Everything is totally accurate, nothing is made up,” she said of what she painted on the canvases. This was an important element of the process, as evidenced by the months she spent researching each painting.

Finch’s husband, Henry, found a map of the original Sacandaga Park, which inspired a triptych of paintings depicting this much-loved place for recreation and relaxation from the mid-1800s through the early 1900s.

The centerpiece of the painting, “The Station,” is the FJ&G railroad station that promoted the Sacandaga Park and later the Sacandaga Amusement Company that it built to attract thousands of visitors to the area. In this work, Finch painted in other details of the park’s activities, as well pieces of her own and friends’ personal family histories.

A second piece of the series, “The Midway,” depicts the park’s burro rides, the “Red Devil” experimental plane, and the High Rock Hotel, among many more activities, businesses, and attractions. Finch’s grandfather used to drive passengers in a stagecoach from the station up to the hotel.

The third painting in the triptych is “Sport Island,” which showcases the park’s sporting events, water activities, and miniature railway. As friends and neighbors learned about her work, they would tell her stories, and Finch would add them into the paintings. “All these little teeny stories were in there,” Finch said.

With so many details and pieces of history, the paintings invite the viewer to discover the significance of each element that ended up in the painting. Finch came to realize that what she had become with the creation of these folk-art paintings was a visual storyteller.

The folk-art style of painting lent itself well to the high level of detail and color that Finch wanted to use. “The colors are just fabulous,” she said. “That’s why a lot of people purchase prints. There’s action, activity, and color.”

However, this once-vibrant Sacandaga Park that Finch depicted with such color and detail is no longer. It was one of the areas that was moved or destroyed so that New York State could build the Conklingville Dam and flood the Sacandaga basin to an elevation of 771 feet above sea level to create the Sacandaga Reservoir, known today as the Great Sacandaga Lake.

The government deemed the building of the reservoir essential because of the yearly flooding of cities along the Hudson River, as there was no way to control the snowmelt coming down from the Sacandaga River. Each spring, the flooding caused millions of dollars of property damage and loss of life. One particular storm that began on Easter Sunday in 1913 dumped the equivalent of Four-to-six weeks’ worth of normal rainfall in just five days, flooding many communities and most tragically, the Albany Pump Station. The resulting contamination of the Prospect Reservoir and an outbreak of typhoid fever in Albany. That sealed the state legislature’s decision to pass a law that allowed for the building of dams to create reservoirs.

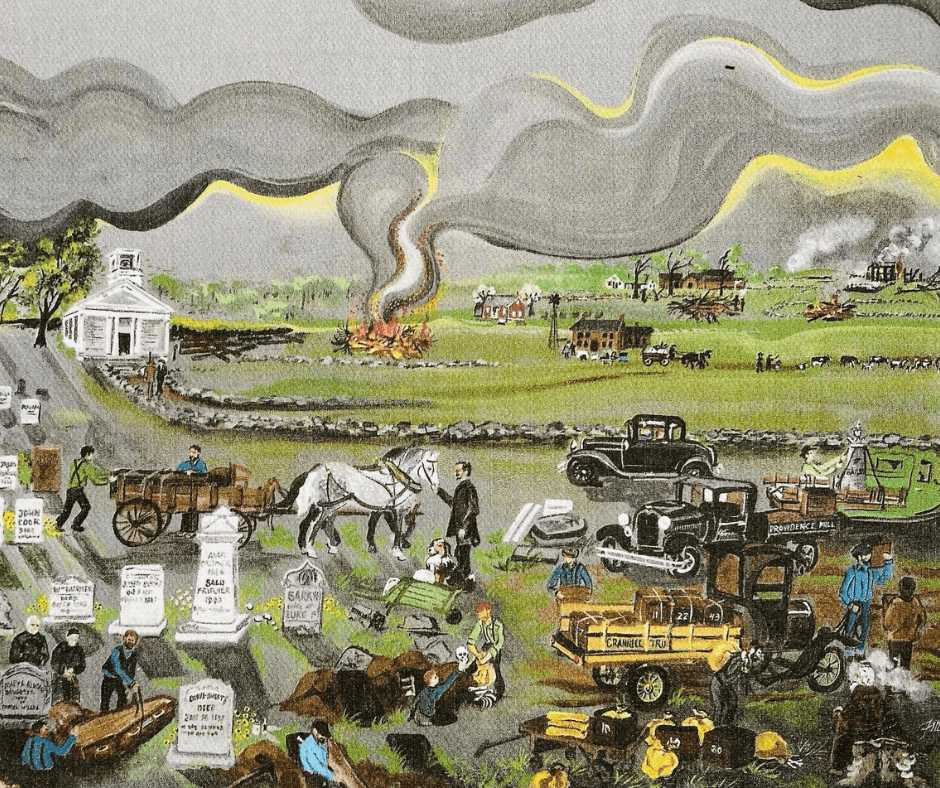

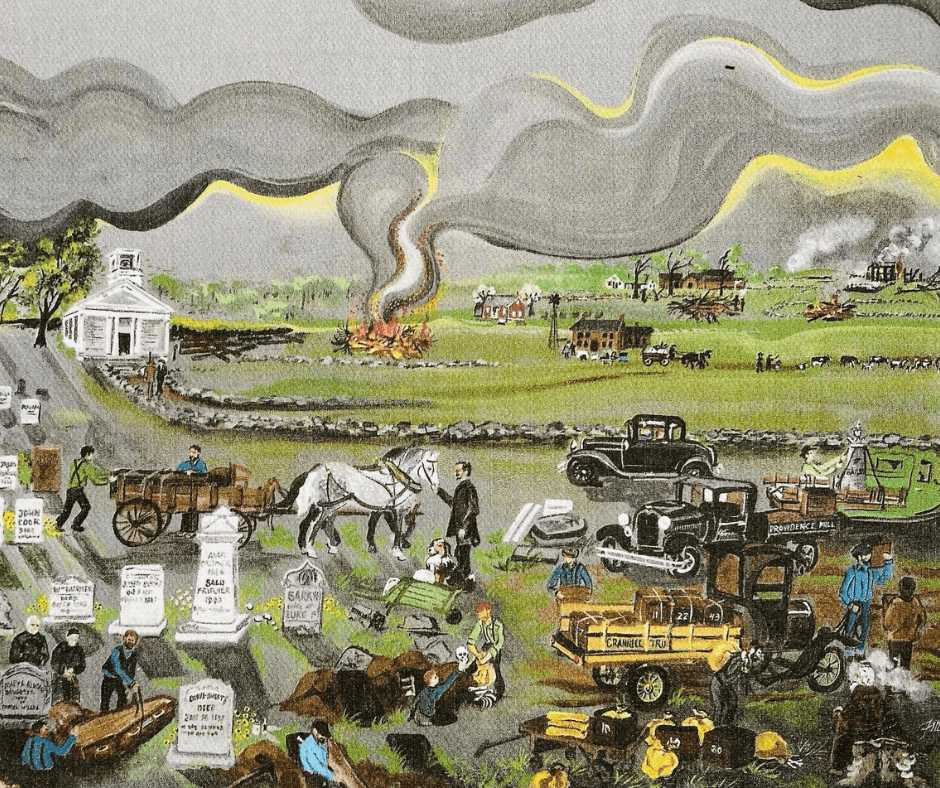

One painting in Finch’s folk-art series documents this sad and sometimes controversial piece of the region’s history. The reservoir’s creation meant the destruction of 10 communities along the Sacandaga River. Residents could either sell their homes or move them. Workers burned any buildings still standing. “Our family was one of the ones that was moved to the valley to make way for the flooding of the Sacandaga,” Finch said.

The process of clearing the area also included relocating 3,872 graves, which Finch depicts in her work, “Boneyard Gang.” The government paid workers $5 for each grave they dug up, and the government permitted family members to be present for the exhumations. In some cases, there were no caskets, and workers bagged up bones and numbered them for relocation. Finch’s great-grandmother’s grave was one of those that had to be moved, and she still has the metal plaque that workers removed from the casket, mounted on a piece of wood.

In the background of this painting are other details of the process of clearing the land, including a family loading its furniture into a wagon and fires burning, producing big billowy clouds of smoke that hang over the entire haunting scene.

Today, the Great Sacandaga Lake, with its 125 miles of shoreline, is the largest reservoir in New York State. The lake has a booming tourist economy and has become an Adirondack paradise for locals and visitors alike, with beaches, boating, fishing, swimming, and other water sports.

Finch is one of those locals who enjoys the nearby lake. She and Henry purchased a home on the water in Northville, where she also has her artist studio. “My business happened by accident,” said Finch, who taught art for many years at the primary, secondary, and college levels.

Finch is one of those locals who enjoys the nearby lake. She and Henry purchased a home on the water in Northville, where she also has her artist studio. “My business happened by accident,” said Finch, who taught art for many years at the primary, secondary, and college levels. “My whole goal wasn’t making money. All of a sudden, people wanted prints and paintings.”

Finch said that the folk-art series documenting history never would have happened without the pandemic. “It’s so unique to have this horrible thing happen and have it turn into one of the most productive times in my entire life,” she said.

What I’m really doing is painting the town.